NJ About to Subtract One of its Tiniest Towns in Rare Merger

TRENTON – For the first time in a decade, and the third time in a quarter-century, two New Jersey municipalities are about to merge.

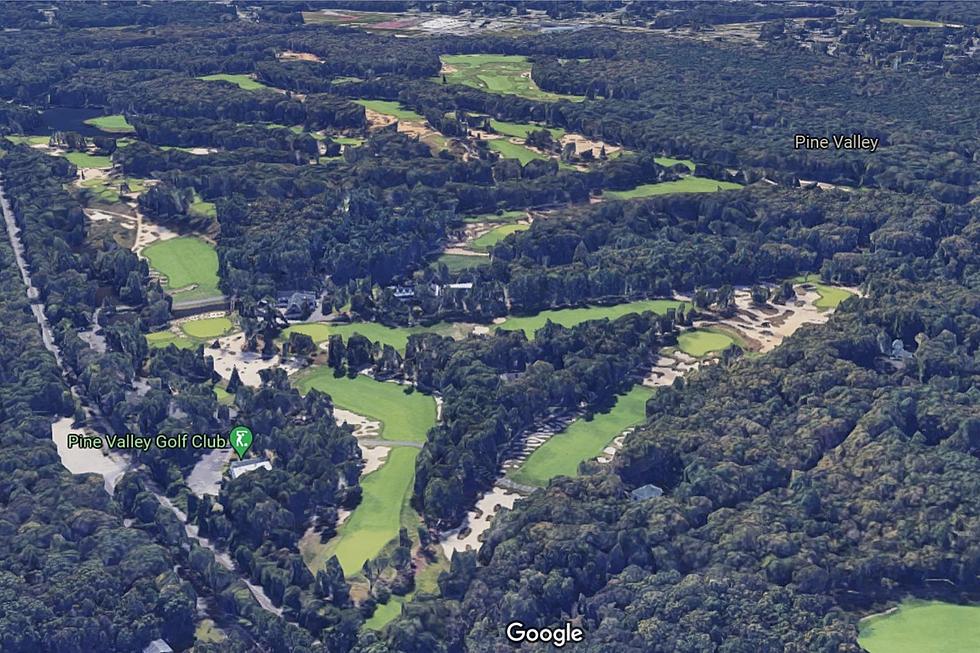

The borough of Pine Valley in Camden County voted to consolidate into Pine Hill. The disappearing town has 21 residents – barely one for each hole on the main course at Pine Valley Golf Club, one of the top golf courses in the world and the borough’s reason for existing.

Like Tavistock – 8 miles to the north, population 9 – Pine Hill exists because locals long ago convinced the Legislature to de-annex it from a larger municipality so the golf club could do its thing.

“In those cases, the municipalities that they were originally associated with were dry. They didn’t want any alcohol,” said Marc Pfeiffer, assistant director of the Bloustein Local Government Research Center at Rutgers University. “But you can’t really have a golf course without a bar.”

Pine Valley voters decided last November to study consolidation with one of its neighbors, Pine Hill or Clementon, and decided to get hitched with Pine Hill in August. Final adoption of the plan in Pine Hill happened this fall.

The merge takes effect on Jan. 1.

“For over a year, the boroughs of Pine Valley and Pine Hill have been exploring the possibility of a consolidation. The boroughs have decided to pursue the consolidation of Pine Valley into Pine Hill,” said the mayors – Michael Kennedy of Pine Valley and Chris Green of Pine Hill – in a prepared statement.

“This decision was arrived at following a careful analysis and extensive discussions,” they said. “The reasons the boroughs have elected this course include fiscal and operational efficiencies and land use compatibility.”

Pfeiffer said in the late 19th century and early 20th century, it was quite easy to establish a municipality in New Jersey.

Particularly in Bergen and Camden counties, Pfeiffer said, there were a lot of local battles over local schools. As villages formed in big rural townships, residents wanted better schools and services. Farmers were happy as things were. Village were able to incorporate, and more than 100 boroughs were formed.

There were also railroad towns, built by speculative developers near stops on rail lines. Other municipalities were rooted in racial discrimination, Pfeiffer said.

“You had people at the time that wanted to be separate. They wanted the Black community separate from the white community,” he said. “So, lots of reasons, good and bad, resulted in a subdividing as it were into what were 567 and now 565 municipalities.”

Pfeiffer said 565 municipalities isn’t actually an unreasonable number for a state with 9.3 million residents, even though it’s fifth-smallest in land area. Compared to the population, the number of local governments ranks 36th, he said.

“When you look at geography, yeah, we have more municipalities per square mile than any other state,” Pfeiffer said. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean we have more government on a per capita basis than other states. In fact, we’re on the bottom half.”

Princeton borough and township voted to merge in 2011, after discussing the idea for a half-century. Pahaquarry Township in Warren County dissolved Hardwick Township in 1997 after its land was taken by the federal government for a dam that was never built – the same reason that Walpack Township in Sussex County is now the state’s least populous town, with seven residents.

The Pahaquarry dissolution was helped along by a state law that applies to sparsely populated municipalities now being used by Pine Valley.

“And it’s great that they’re able to take advantage of it because it’s a much easier way to do a consolidation than the normal process that other larger places would have to go through,” Pfeiffer said.

It’s not clear when the next consolidation might happen. There are often complications, even when it would seemingly make sense. For instance, Pfeiffer said Walpack may be hard to arrange because a mountain separates it from the neighbors it would join with.

“We don’t have consolidations because it has been this way for so long. Things get the way they are because simply they got that way,” Pfeiffer said. “And making changes is very difficult. They won’t necessarily reduce costs, depending on the individual circumstances.”

“Given differences in the community and their assessed value, if you propose a consolidation and as a result, one municipality’s average residential taxes are going to go and another one’s are going to go down, it’s going to be really hard for the people whose taxes are going to go up to vote in favor of it,” he said.

Pfeiffer said a Rutgers study found bigger isn’t always better, especially once you get above a certain size.

“Municipalities who have a larger population tend to spend more on a per capita basis than smaller ones because they’re larger, they do more things, their labor contracts may be more expensive than smaller places,” he said. “So, on a per capita basis, the tendency is – and it’s not 100% in all circumstances – but smaller places tend to have lower costs per capita.”

“The sweet spot I suppose tends to be in the 7,500 to 12,000 level. That seems to be sort of on the low end,” Pfeiffer said. “Once you get above about 12,000 people, you wind up with some of the highest cost per capita.”

New Jersey has 260 municipalities with fewer than 7,500 residents, 94 municipalities in that optimal range identified by the Rutgers study and 211 municipalities with more than 12,000 residents.

Pine Hill, incidentally, will have 10,811 residents – and add one great golf course – once the merger takes effect at the start of 2022.

COMPARE: Highest 2020 property taxes in each county

NJ towns that actually cut property taxes in 2020

More From WPG Talk Radio 95.5 FM